Before I go any further, I’d like to mention that any opinions I have about the event and my perceptions are purely my own. Decisions I made are all on me. I love and respect the Hoka Hey family and everyone out there cheering us on and supporting us. I’m proud to be a part of it.

When I decided to ride my 1955 FL, a Panhead I’ve named Luxe, I knew nothing would be simple. I knew a finish was unlikely, but I was excited to give it a try. I envisioned riding until the bike would go no farther, stuck in a lonely town with tall trees, or perhaps a desert turnout with dire warnings of ‘serpientes venenosas’, without cell service and unsure how I would proceed. But I had to do something different, or what was the point? I did not have the need in my soul to take the risks required to end up as an Elite Finisher – one of the first 20 riders to arrive at the finish line. I couldn’t see a huge improvement over my 2018 finish, so I chose a challenge I felt would be epic, regardless of when my journey ended.

One of the goals of the Medicine Show LLC, the organization that runs the Hoka Hey Challenge, is for participants to raise funds. The recipient can be the non-profit that the organization chooses that year, or a rider can choose something important to them. I’d learned about the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) and knew that a friend of mine had ridden on the Medicine Wheel Ride, which is a non-profit that raises money to fight for indigenous women and support victims and their families. Having been a victim of domestic violence and writing a memoir that included that experience, I have been stunned at the number of women who have shared their stories with me. And violence against indigenous women occurs at ten times the rate of other populations. I chose to raise money for the Medicine Wheel Ride. I was honored to work closely with Shelly Denny, the founder of the organization. The day before we rolled out, I met Lynette Red Cloud Roberts and Lorna Curry at a park in Rapid City for a prayer ceremony. I fell in love with the aroma of burning sage, and while I could not understand the words the elder spoke, I was grateful for them and my choice to support this group.

Before the first wheel passed the starting line, I was having trouble. My one-kick wonder was already rebelling and making me work to get the engine going. Upon arrival at the host hotel two days before the start, I was questioning my sanity. I had participated in the Cross County Chase in 2021, which was quite different. Although I was far from home without my husband to coach me when I failed to start the bike on the first kick, there were plenty of riders with experience they were willing to share, as well as the sweep truck that wouldn’t leave a rider and their motorcycle rotting on the side of the road. I had a general idea where in the United States I’d be. With the Hoka Hey, while I knew where the three checkpoints were, I also knew there would be 2,500 to 3,000 miles between them. That left a lot of ambiguity. Not too bad on a late model Road Glide Special, but a bit dicey on a vintage machine with parts that aren’t that easy to find even in your home town.

I chose to hang back for the departure from Black Hills Harley-Davidson on the morning of June 26, 2022. The directions had us starting out on I-90 for a few miles, and I wasn’t going to blow up my engine the first day. I quickly lost sight of my fellow challengers and enjoyed the cool morning ride north. I was excited to pass a few riders at the first gas stop, but they zoomed by before long.

Gasoline management is one of the challenges with a Panhead participating in this event. No gas gauge and only one trip odometer. On most other bikes, you’d have a gas gauge and a readout telling you your range. With trip A and trip B, you can use one to track the whole event, checkpoint to checkpoint, oil changes, whatever. The other trip could be used to keep track of the mileage from turn to turn on the directions. Get to the turn, reset the trip. Cake and pie – piece of cake, easy as pie. For me, not so much. I had estimated my gas range to be 130 miles as read by my odometer. The thing was, my odometer was off by a tenth of a mile on a one mile marker test and a lot more over any distance. It was easy enough for gas; I knew I was going to be pushing my limits if the trip reached 130 miles, no matter how many actual miles I’d ridden. If I came upon a gas station when my trip odometer said 50 miles, I stopped. I wouldn’t make it another 100 miles, which was my assumption of the max distance between gas stations based on my 2018 Hoka Hey experience. This brings up my other challenge – lots of math.

I don’t mind math. I went to an engineering school and got an A in calculus. Simple addition and percentages don’t bother me. Math on a Panhead kind of sucks. There are plenty of other things to think about, like not dying. For example, I’m on a 225 mile stretch before the next turn. I stop to get gas when my trip says 105 miles. So that’s actually about 115 miles. Make a mental note of 115 miles. On my trip, that’s actually going to be 115 miles minus 10 percent, so about 103 miles. I ride 50 miles per the odometer, but that’s really somewhere around 55 miles, and there’s a gas station, so I should probably stop now based on 100 mile rule mentioned in the previous paragraph. Subtract 50 from 103. Or was it 113? Or should I subtract 55? Ok, 103 real miles minus 55 real miles (all a super vague estimation) leaves 48 miles. But will that be 43 miles on my odometer? Did I already work the adjustment into that number? Maybe. Ok, let’s pull out the atlas and see. When I get to that town, I need to start looking for the next turn. There’s another 10 minutes down the drain. Daylight’s burning.

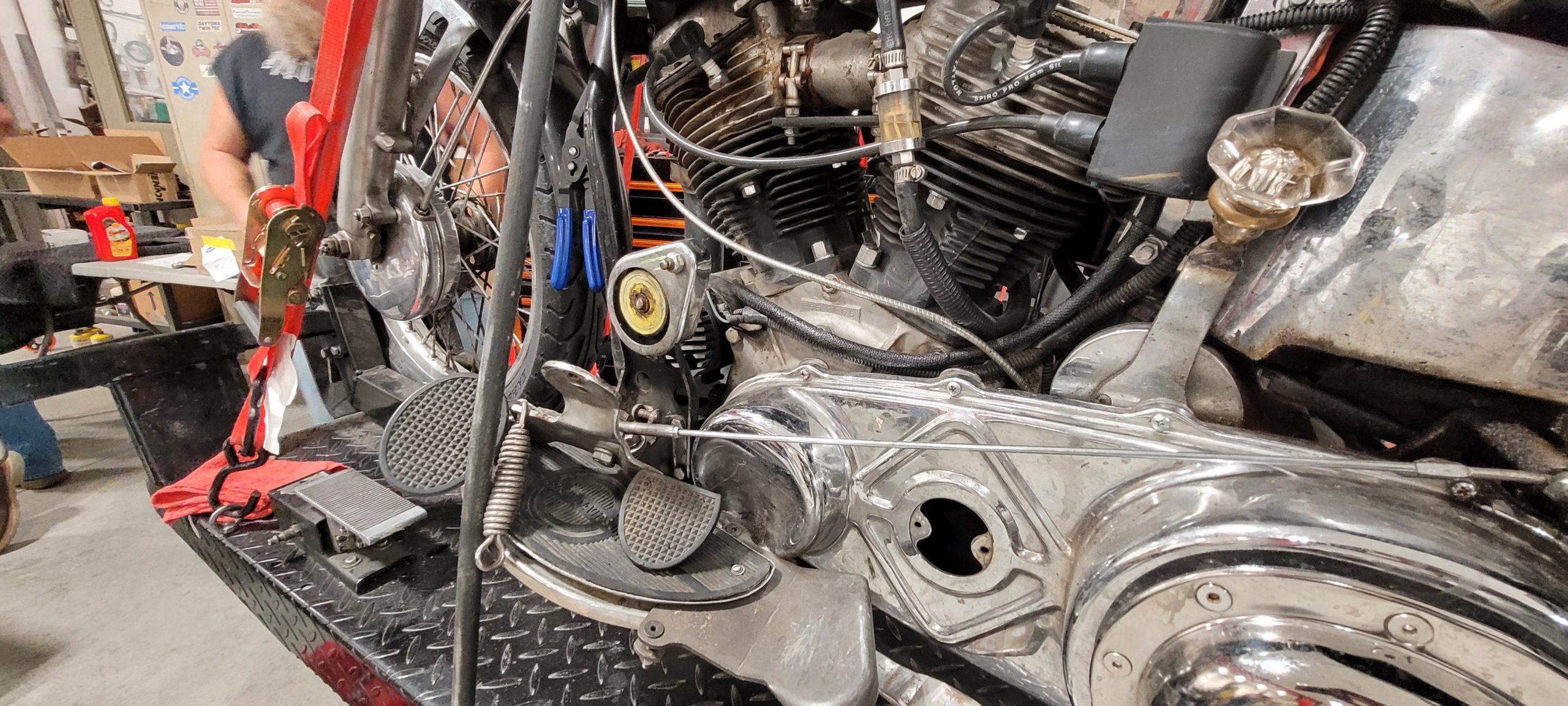

I could write a novel about this adventure. So many beautiful views, frustrating moments, challenges, and great people I met. I’m extremely grateful for Siouxicide Choppers for fixing the tab on my frame that holds my gas tank on as well as my clutch pedal pivot pin that sheared off three blocks from their shop. Timing is everything! Dragoon Motorcycle in Tombstone, Arizona (cant find a website to link) also helped out in a pinch when I finally had enough of adjusting my chain day in and day out (and eventually every half a mile) and swapped it out for the new one in my saddlebag. That was something that should have been done before I left. Kicking myself for all the unnecessary grief that caused me.

Once the chain was replaced, life got better. Well, except for the part where it was near impossible to start the bike every morning. I’d wake up early, ready to put 500 – 600 miles behind me, and I’d be there half an hour kicking and kicking. I finally started letting people help. Nobody got it done quickly, but it would eventually go. I dreaded the mornings. Once it was warmed up, no problem, but first kick of the day was doing me in every single day. There were a couple of times the bike randomly stalled. The first time was when I discovered the gas tank was falling off in South Dakota. The second time was right after I left Siouxicide Choppers. That time I got a tow back to a campsite and went over the whole bike but found nothing. It started the next day, and I went on my way.

Zion Harley-Davidson was the second checkpoint, and they were happy to put on new tires and do some wheel maintenance as well as an oil change. That was a relief since most dealerships won’t touch a panhead. Special circumstances. I really enjoyed working with them. Rawhide Harley-Davidson, the first checkpoint, rolled out the red carpet and were amazing hosts too. They all made me feel like a rock star, although I was getting more and more concerned that I was going to let everyone down.

A crack in the transmission plate had been discovered early on, and then the exhaust started disintegrating. I stopped at a car parts store and wrapped the pipe up, which helped for a day. I felt better physically and mentally than I ever had on a Hoka Hey Challenge, but Luxe was fading fast. Approaching the California/Oregon border, on a downhill coast, the bike shut down again. I had time to mess around with the ignition switch and the gas and eventually got it going again, but doubts about my safety were growing exponentially. I had grown very attached to my motorcycle, and the thought of riding it into the ground stopped making sense. It’s a valuable vintage bike and hard to replace, and where was it going to decide to quit the next time? Would I be able to get to a safe place, or would I get run down by another impatient driver – California drivers had shocked me with their disregard for others on the road.

I called a friend who had finished the challenge, and she told me that a friend of mine had wrecked and was paralyzed. Thankfully it appears he is recovering, but he is in rough shape. Two participants had died. At that moment, I couldn’t figure out why I was doing this. I’d endured hundreds of miles of desert with insanely high temperatures and had, for some strange reason, lost my patience with peeing in the woods. I didn’t want to kill my motorcycle, and I didn’t want to die because I was too stubborn to admit defeat – to admit that yes, I embarked on a near impossible task and, well, I didn’t complete it. I’m not saying it can’t be done; it wasn’t done by me. I had gone around 7,000 miles in 15 days through 14 states, which is more than anyone else has done on a kickstart, rigid frame, foot clutch/hand shift motorcycle on the Hoka Hey. As my brother said, “Mount Everest is littered with the dead bodies of once highly motivated people.” I have a good life and people who care about me. It was time to think about my family and all the things I still want to get done.

I thought I would be more disappointed. I’m proud of myself for turning away from the possible glory of finishing this, recognizing that my risk of not finishing because I was dead or severely injured was increasing at a huge rate day after day, and deciding that all the peer pressure on social media regarding the event was not going to rule my judgement. The thought that to be competitive means to ride like a suicidal maniac disturbs me and causes me to feel that this was my last Hoka Hey. However, the event is always evolving, and maybe things will change. Or they won’t, and that’s fine. There will still be people eager to give it their best shot. I’ve finished a couple of times, and I’m good.

I am looking forward to giving a Luxe a makeover in the next year and putting her out to pasture for short runs to Sturgis and local bike shows. She deserves a relaxing retirement after that ride.